Nicotine, the psychoactive component of tobacco, shows much promise as a nootropic.

- Stimulating the brain’s nicotinic receptors. This activation appears to enhance cognitive function and protect neurons from damage.

Overview

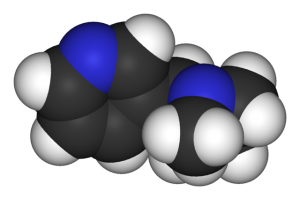

Nicotine is a chemical compound found in high concentrations in tobacco plants and other members of the nightshade family (Solanaceae). Nicotine belongs to a group of nitrogen-based compounds known as alkaloids, which exert a variety of physiological effects in humans and animals.

Nicotine is best known as the main psychoactive ingredient of cigarettes, inducing pleasure and reducing stress and anxiety, while simultaneously improving concentration and reaction time.

Nicotine also plays a central role in the addictive nature of cigarettes – its rapid absorption in the lungs causes the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is linked to the brain’s reward and pleasure pathways. As a result, long-term tobacco users find it difficult to stop smoking, and can suffer from withdrawal if they attempt to quit.1

Despite its bad reputation, recent research suggest that nicotine may be a potent nootropic, and can be beneficial for people suffering from ADHD, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, depression, schizophrenia, and overall cognitive impairment. In addition, nicotine also appears to support some aspects of cognitive function in healthy individuals, such as attention and memory.

The Nicotine Danger Myth

Given its association with smoking – the leading cause of preventable death – there exists a popular misconception that nicotine is a dangerous, highly addictive substance.2

In reality, nicotine by itself is a relatively mild compound. This is confirmed by studies that have shown nicotine patches – which deliver nicotine slowly and without added compounds – to be safe and non-addictive, in addition to trials of isolated nicotine given to animals.34

Nicotine only becomes a problem when mixed with thousands of other compounds in cigarettes, which are specifically designed to enhance its action and make smoking more addictive. Furthermore, inhaling smoke is a highly efficient and rapid way of delivering nicotine to the brain, which is another reason why its addictive properties become vastly enhanced in cigarettes. In fact, it only takes about seven seconds for nicotine to reach the brain from the lungs.

Lastly, it is a well-recognized fact that the multitude of health risks associated with smoking are caused by harmful chemicals found in cigarettes, not nicotine.5

How Nicotine Might Help With Brain Health

Stimulation of nicotinic receptors

Nicotine works primarily by stimulating the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) found in brain cells. These proteins typically respond to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, but also have a high affinity for nicotine, meaning that they readily bind with it and similar compounds.

The main outcome of this activation is the release of various neurotransmitters, including dopamine, glutamate, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Moreover, researchers propose that nicotine is able to affect intracellular mechanisms such as calcium signaling, which may modify neuronal function. In turn, these changes may protect neurons from damage caused by neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s.7

Antioxidant activity

Furthermore, researchers speculate that nicotine might exert its effects outside the nAChRs as well. One popular suggestion is that it functions as an antioxidant – a compound that protects brain cells against damage caused by oxidative stress. However, this mechanism requires further research to be confirmed.8

Nicotine Benefits for Brain Health

Although nicotine has yet to shed its negative reputation in mainstream science, the last two decades of research point to a multitude of nootropic benefits. Most notably, a large number of studies have shown nicotine to help with depression, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, ADHD, schizophrenia, Tourette syndrome, and overall cognitive impairment.91011121314

Moreover, a number of studies indicate that nicotine can also have nootropic action in healthy individuals. The most notable findings include improved attention and prospective memory – the retrieval and implementation of a previous intention to do something.15

Research

Animal Research

Given nicotine’s safety, the majority of research has focused on human medical trials. Nonetheless, findings in animals indicate that nicotine may:

Human Research

The findings of human nicotine trials suggest that it is a safe and effective way of helping with a number of cognitive disorders. Furthermore, nicotine also appears to be capable of improving attention and other aspects of an already healthy brain.

Nicotine patches (7 mg) appear to improve attentiveness in healthy adults

In this double-blind study, 11 healthy non-smoking adults were given placebo or nicotine patch (7 mg) daily for 4.5 hours. Next, they completed several tests to measure their attentiveness. Nicotine resulted in improved test performance, particularly on the Conners’ computerized Continuous Performance Test (CPT) – a popular way of measuring attentiveness.

- The researchers concluded that “the attention-improving effects of nicotinic treatment are also clearly evident in non-smoking subjects with-out pre-existing attentional impairment”18

Nicotine spray (1 mg) appears to enhance prospective memory

This double-blind, placebo-controlled study examined the effects of nicotine on prospective memory (ProM) – the retrieval and implementation of a previous intention to do something. Thirty-two habitual smokers and 33 non-smokers were given either nicotine nasal spray (1 mg) or inactive placebo spray, and then performed a ProM test. Nicotine was found to significantly improve ProM performance in both smokers and non-smokers.

- The researchers concluded that “Equivalent effects are observed in nonsmokers and smokers. Nicotine improves ProM when the volunteer has no competing task demands”19

Nicotine patches (7 mg) may help reduce impulsive behavior in people with ADHD

This double-blind study investigated the idea that nicotine could improve cognitive and behavioral inhibition in teenagers with ADHD. This inhibition is one of the key signs of the disorder, and is largely responsible for impulsive behavior seen in ADHD patients. Eight teenagers with ADHD received 3 treatments on separate days in random order – nicotine patch (7mg), placebo, and methylphenidate (10-20 mg), a common ADHD medication. Nicotine was found to be at least as effective as methylphenidate at improving inhibition performance.

- The researchers concluded that “nicotine administration has measurable positive effects on cognitive/behavioral inhibition in adolescents with ADHD”20

Nicotine appears to improve some cognitive impairments caused by Alzheimer’s

The goal of this frequently-cited single-blind, placebo-controlled study was to examine the effectiveness of nicotine in helping with Alzheimer’s. Three groups of people – 24 Alzheimer’s patients (DAT), 24 healthy adults, and 24 young healthy participants – were given placebo and nicotine injections (0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg) on separate occasions, followed by tests of cognitive function. While the healthy individuals were not significantly affected by nicotine, the DAT group saw improvements in measures of perception, attention, visual information processing, and reaction time.

- The researchers concluded that “Despite the absence of change in memory functioning, these results demonstrate that DAT patients have significant perceptual and visual attentional deficits which are improved by nicotine administration”21

Nicotine may be a promising therapy for Parkinson’s

Fifteen older individuals (mean age of 66) with early to moderate Parkinson’s were first given up to 1.25 mcg/kg/min nicotine by IV, and then wore nicotine patches with doses up to 14 mg/day for 2 weeks. The injection resulted in improvements in reaction time, processing speed, and other measures of mental performance. Meanwhile, wearing the patch led to improvements in measures of motor function.

- The researchers concluded that “Nicotinic stimulation may have promise for improving both cognitive and motor aspects of Parkinson’s”22

Nicotine patches (15 mg) appear to improve mild cognitive impairment

The goal of this double-blind study was to test if nicotine could reduce mild cognitive impairment (MCI) – a transitional stage between normal cognitive function and mild dementia. Seventy-four people with MCI were randomly assigned to take nicotine patches (15 mg) or placebo treatment daily for 6 months. The nicotine group saw improvements in attention, memory, and mental processing.

- The researchers concluded that “measures of attentional, memory, and psychomotor performance did show an effect of nicotine and this finding provides strong justification for further treatment studies of nicotine for patients with early evidence of cognitive dysfunction”23

![By Esquilo [1] [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://supplementsinreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/nicotinic-receptor-structure-300x177.png)

Dosage for Brain Health

- Most successful studies of nicotine’s nootropic activity tend to use transdermal patches with daily doses ranging from 7 to 15 mg

- Commercially-available nicotine patches have similar dosages to those used in research studies, although they may go as high as 21 mg

Side Effects

Despite the negative outlook of early research, recent studies demonstrate that nicotine taken in the form of gum, spray, and patch is relatively safe and non-addictive. Only minor side effects have been reported, such as redness or itching after patch use; indigestion, mouth irritation, or headache after chewing gum; and stuffy nose or irritation of nasal mucosa tissue after spray use.2526272829

Available Forms

Nicotine is typically sold in patch, gum, lozenge, spray, and inhaler form. While all forms are safe, transdermal patches are currently the most researched way of applying nicotine for nootropic benefits.

Popular branded forms of nicotine include:

- Nicoderm® – offers three nicotine patch products that release 7-21 mg over a 24 hour period

- Nicorette® – best known for their gum containing 2-4 mg nicotine, but also offer lozenge, inhaler, and spray products

Supplements in Review Recommendation

- Nicotine, 7 mg, transdermal patch applied daily.

Nicotine appears to help with a variety of mental disorders and enhance cognitive function. Despite the negative association between nicotine and smoking, current research suggests that nicotine is both safe and effective at ameliorating conditions ranging from depression to Parkinson’s. Moreover, the fact that is has been demonstrated to enhance certain aspects of cognition in healthy subjects makes nicotine a very promising nootropic.

7 mg is the most popular successful dose used in research. Most human studies tend to use transdermal patches with doses ranging from 7 to 15 mg. Given nicotine’s safety, it’s perfectly reasonable to start out with 7 mg patches, assess their efficacy and tolerance, and then consider going up to 14 mg and later 21 mg.

References

Leave a Reply