BCAAs may be useful as a pre-workout aid, but the need for supplementation remains controversial.

![By Harbin Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://supplementsinreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/leucine-bcaa-structure-300x269.png)

- Supporting muscle growth. BCAAs decrease the breakdown of muscle associated with strenuous exercise or dieting.

- Enhancing muscle recovery. BCAAs protect against exercise-induced muscle damage.

Overview

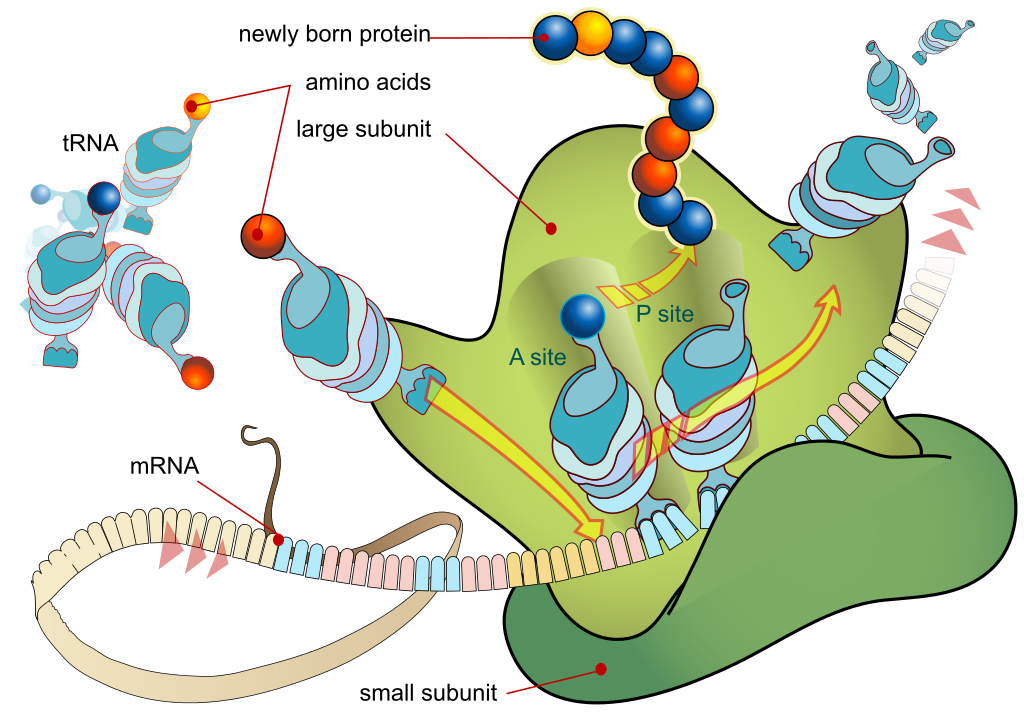

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) are amino acids with a branching chemical structure. BCAAs include three specific amino acids – leucine, isoleucine, and valine – which cannot be be produced by the body and must come from the diet. Since protein is made up of amino acids, BCAAs are present in all protein-containing foods, making animal products an ideal source.

BCAAs are present in large concentrations in muscle tissue, where they are directly involved in muscle protein synthesis and energy production.1Leucine in particular is the most potent of the three, thanks to its unique ability to directly stimulate protein synthesis.

Because of these effects, BCAAs have become a popular sports supplement with supposed benefits for muscle growth and recovery.

The BCAA Supplementation Dilemma

Despite their widespread use in sports supplements, there are two central issues with BCAA supplementation:

First, it’s possible to get enough BCAAs from dietary protein sources, which puts the need for supplementation in question. As one highly-cited study highlights, when protein intake is sufficiently high, adding BCAAs does not result in any added benefit for muscle protein synthesis. Eating about 1-1.5 g/kg body weight of protein a day appears to be sufficient to maximize BCAA intake.

The second issue is that most BCAA studies do not control caloric intake, or were designed to have low protein intake. This means that the reported effectiveness of BCAA supplementation could simply be the result of the participants not getting enough BCAAs from dietary protein.

Having said that, BCAA supplementation can still be effective under certain circumstances. One prominent example is working out while fasted, which has recently gained popularity. Because exercising in such conditions may lead to increased muscle breakdown, supplementing BCAAs can provide the required nutrients while still maintaining a fasted state.2Other examples include athletes that don’t get enough protein, such as vegetarians, or bodybuilders and wrestlers during a calorie-restricted (“cutting”) diet.

How BCAAs Might Help PWO Formulas

Regulating muscle protein balance

The major bio-activity of BCAAs is the combination of decreased muscle protein breakdown (MPB) and increased muscle protein synthesis (MPS) during and after strenuous exercise—particularly resistance training.4The relationship between these opposing processes is what determines whether muscle is gained or lost, and is collectively called the net protein balance.

Although resistance exercise improves this balance, it will still remain negative in the absence of proper protein intake. This is exactly why pre or post-workout ingestion of sufficient amounts of essential amino acids – be it as dietary protein, a protein supplement, or BCAAs—is so critical.5

Leucine in particular is the most potent BCAA, and is the only amino acid known to directly stimulate MPS via the mTOR pathway, which promotes muscle hypertrophy. In particular, mTOR is known to trigger Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which plays a key role in muscle growth.67

Potentially reducing tryptophan uptake

One hypothetical activity of BCAAs is a reduction in the brain’s uptake of tryptophan, an amino acid required for synthesizing the neurotransmitter serotonin. Serotonin, in turn, is believed to play a major part in the development of central fatigue during prolonged exercise. However, no conclusive results have been found as of yet.89

BCAAs’ Proposed Benefits & Uses

The main advertised benefit of BCAAs is improved muscle growth during resistance training, which results from decreased breakdown and increased synthesis of protein. Moreover, BCAAs may also help exercise recovery by protecting against muscle damage caused by both aerobic and anaerobic exercise.

However, it’s important to stress that BCAAs are naturally present in protein, whether it comes from your diet or a supplement. As such, as long as your protein intake is sufficient, you are already receiving these benefits. BCAA supplementation is best suited for situations where you’re not getting enough protein/BCAAs, such as working out fasted, or when you’re dieting.

Research

Animal Research

Animal trials of BCAAs confirm many of their effects in humans, and suggest other potential benefits and mechanisms of action. Specific findings indicate that BCAA supplementation in rats may:

- Stimulate skeletal muscle protein synthesis via the mTOR pathway in both normal and food-deprived (fasted) animals1112

- Increase time to exhaustion during endurance exercise1314

- Promote physical activity, such as voluntarily-increased running distance, and decrease central fatigue15

Human Research

Human trials of BCAA supplementation show mostly positive findings. However, it is important to reiterate that BCAAs can be obtained from dietary protein sources, and that successful studies could be the result of insufficient protein intake of the participants.

BCAA (5 g) may reduce exercise-induced muscle soreness and fatigue in untrained individuals

The goal of this study was to test the effects of BCAA supplementation on delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) and muscle fatigue from bodyweight exercise. Sixteen women and 14 men with no regular exercise experience were assigned to take either a placebo or BCAA drink (5 g) and performed 7 sets of 20 squats with 3-minute resting periods. After 12 weeks, groups were switched so that each person was tested with both placebo and BCAA.

Muscle soreness and fatigue were measured by a visual scale before, and for 4 days following the exercise. DOMS and muscle fatigue were lower after the BCAA trial compared to placebo.

- The researchers concluded that “ingestion of 5 g of BCAAs before exercise can reduce DOMS and muscle fatigue for several days after exercise…BCAA may attenuate exercise-induced protein breakdown, while leucine may stimulate muscle protein synthesis”16

BCAA (12 g) may reduce muscle damage caused by endurance exercise

This popular study tested whether BCAA supplementation can reduce muscle damage following endurance exercise. Sixteen male participants were assigned to take placebo or BCAA (12 g) daily for 14 days. They performed 120 min of cycling a week before, and on day 7 of supplementation.

Their levels of levels of creatine kinase (CK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)—two well-known markers of muscle damage—were recorded for 7 days following both cycling tests. The study found that BCAA supplementation significantly lowered LDH from 2 hours to 5 days, and CK from 4 hours to 5 days post-test.

- The researchers concluded that “These results indicate that supplementary BCAA decreased serum concentrations of the intramuscular enzymes CK and LDH following prolonged exercise, even when the recommended intake of BCAA was being consumed. This observation suggests that BCAA supplementation may reduce the muscle damage associated with endurance exercise.”17

This frequently-cited study examined the effects of BCAA supplementation on body composition during a calorie-restricted diet. Twenty-five competitive wrestlers followed a cutting diet for 19 days, and were split into 4 groups – low-calorie control, low-cal-high-protein, low-cal-low-protein, and low-cal with BCAAs (0.9 g per kg bodyweight per day).

Parameters such as percent body fat were measured before and after the diet. While all groups lost body fat, the BCAA group had the most impressive results, losing 17.3% of their body fat and 34.4% of their abdominal fat in particular.

- The researchers concluded that “energy restriction diets induce a reduction in the body mass and favorable modifications in body composition. A high-branched-chain amino acid diet produces the highest losses in body fat”18

This was one of the only studies to test the whether BCAA, and particularly leucine supplementation is necessary for maximizing exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy (growth). Untrained men and women were assigned to either placebo or whey protein (16.6 g) plus leucine (3.4 g) groups and performed intense leg resistance exercise.

While whey plus leucine was obviously more effective than placebo for inducing post-exercise MPS, it was not superior to 20 g of whey protein alone, which the researchers tested in a previous, identical study. These results confirm the idea that sufficient dietary protein intake provides enough BCAAs, making BCAA supplementation unnecessary in most cases.

- The researchers concluded that “these data demonstrate that increasing the amount of leucine ingested with whey protein prior to exercise does not increase the response of positive net muscle protein balance”19

The goal of this study was to examine the effects of BCAA supplementation plus resistance training on body composition and muscle performance. Nineteen men without previous resistance training experience took placebo or BCAA (9g) and followed a training program for 8 weeks. BCAA was taken in doses of 4.5 g 30 min before and after exercise. There were no significant differences in body composition, muscle strength or endurance between the two groups.

- The researchers concluded that “our results suggest there to be no need for supplementing with BCAAs during extended periods (i.e. 8 weeks) of heavy resistance training”20

This study examined whether BCAA supplementation could help athletes maintain muscle mass and fitness on a calorie-restricted diet. Seventeen men with previous resistance training experience were assigned to BCAA (14 g) or placebo group and underwent weight training for 8 weeks. BCAA was taken in doses of 7 g before and after a workout. They also followed a calorie-restricted “cut” diet.

While the placebo group lost 0.9 kg of lean body mass, BCAA gained 0.4 kg. In addition, BCAA gained 1 rep-maximum bench press strength (+7.1 kg) and bench press (+15.1 kg), versus a loss of 1RM (-3.7 kg), and a smaller gain in bench (+4.8 kg) for placebo.

- The researchers concluded that “BCAA supplementation in trained individuals performing resistance training while on a hypocaloric diet can maintain lean mass and preserve skeletal muscle performance while losing fat mass”21

BCAA (7g) does not appear to delay onset of fatigue during intermittent running exercise

This study tested whether carbohydrate drinks with and without BCAA could help fight fatigue during intermittent high-intensity running. Three physically active women and 5 men performed intermittent shuttle runs, after being randomly given one of 3 drinks: placebo, carbohydrate, or carbohydrate with BCAA (7 g) 1 hour and 10 minutes before exercise.

The protocol was repeated two more times so that all participants tested the different treatments. Although subjects managed to run longer when given carb drinks, BCAA did not have any added benefit on delaying fatigue.

- The researchers concluded that “ingestion of carbohydrate beverages 1-h prior to and throughout exercise delays fatigue during intermittent high-intensity exercise…The addition of BCAA to the carbohydrate drinks, however, does not appear to provide any additional benefit”22

Dosage for Pre-Workout

- Most successful studies use 5-14 g of BCAAs daily, or specifically before a workout

- Most single-ingredient products and pre-workout formulas supply doses of anywhere from 5–10 g

Available Forms of BCAA

BCAAs are typically sold in capsule or powder form by themselves or in a pre-workout formulas. The amount of leucine in BCAA supplements is higher than isoleucine and valine, with a typical ratio of 2:1:1. Some formulations also add glutamine, another amino acid that is believed to have beneficial effects for exercise.

Supplements in Review Recommendation

- BCAAs, 5 g pure powder pre-workout.

Supplementing BCAAs can be useful if you’re training fasted or otherwise not getting enough protein. In such cases, you may very well see improved muscle growth and exercise recovery.

If you think BCAAs are right for you, 5 g is a good starter dose. Most supplements provide about 5g per scoop, which can easily be increased for desired effect.

References

Leave a Reply